SUGi x University of Oxford pilot study on well-being

Research and text by Kathy Willis, Professor of Biodiversity in the Department of Biology and the Principal of St Edmund Hall, University of Oxford, and Molly Tucker, Research Assistant in the Oxford Long Term Ecology Laboratory

Key takeaways:

- 30 minutes beside all 3 of SUGi’s dense, native, wild urban forests significantly reduced participants’ anxiety compared with nearby control sites.

- Heart-rate data revealed greater physiological calming beside the Southbank Forest than in its minimally vegetated control setting.

- High-quality wild spaces with native tree diversity delivered measurable mind-body benefits

In recent years, a large body of research has emerged to indicate that time spent in urban green spaces can automatically trigger physiological and psychological mechanisms in our bodies that lead to significant beneficial physical and mental well-being outcomes (Willis, 2024). As cities continue to grow, and access to urban green spaces becomes increasingly impacted, understanding the best type of green space to create in cities, and particularly the role of small patches of newly created vegetation, such as pocket forests, is critically important.

This study investigates how SUGi Pocket Forests might promote improvements in physical and mental well-being. Healthy adult volunteers (aged 18 and over) were invited to take part by spending 30 minutes sitting beside one of three SUGi Pocket Forests—Forest of Thanks (Barking and Dagenham), Serenity Forest (Kensington), and Southbank Forest (Central London on the south bank of river) —and in each site at a nearby comparison site without dense tree planting.

In total, 75 participants took part in the study conducted during September 2025. Participants’ anxiety scores, heart rate, and heart rate variability were measured before and after each 30-minute session to evaluate how time spent in the pocket forests affected them compared with spending the same amount of time sitting at nearby control sites without dense trees.

What the Study Set Out to Discover

Urban green space is increasingly recognised as critical to human health, with prior research showing that access to nature can support psychological and physiological well‑being. But cities are growing fast, and access to high‑quality wild green space isn’t always available. In this context, the question becomes: What type of urban nature is most effective at supporting well‑being? This study focused specifically on pocket forests — densely planted clusters of native trees and shrubs — to test whether they could improve mental and physical well‑being compared to nearby urban sites with minimal vegetation.

How the Study Was Conducted

Seventy‑five adult volunteers spent 30 minutes seated beside one of three pocket forests — Southbank Forest, Serenity Forest, and Forest of Thanks — and separately, 30 minutes at nearby comparison sites that lacked dense tree cover. The researchers measured changes in:

- Anxiety levels, using the standard clinical State‑Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

- Heart rate (beats per minute)

- Heart rate variability (a key indicator of parasympathetic nervous system activity)

These measurements were taken both before and after each session to assess how time spent in pocket forests versus typical urban settings affected participants’ physical and mental states.

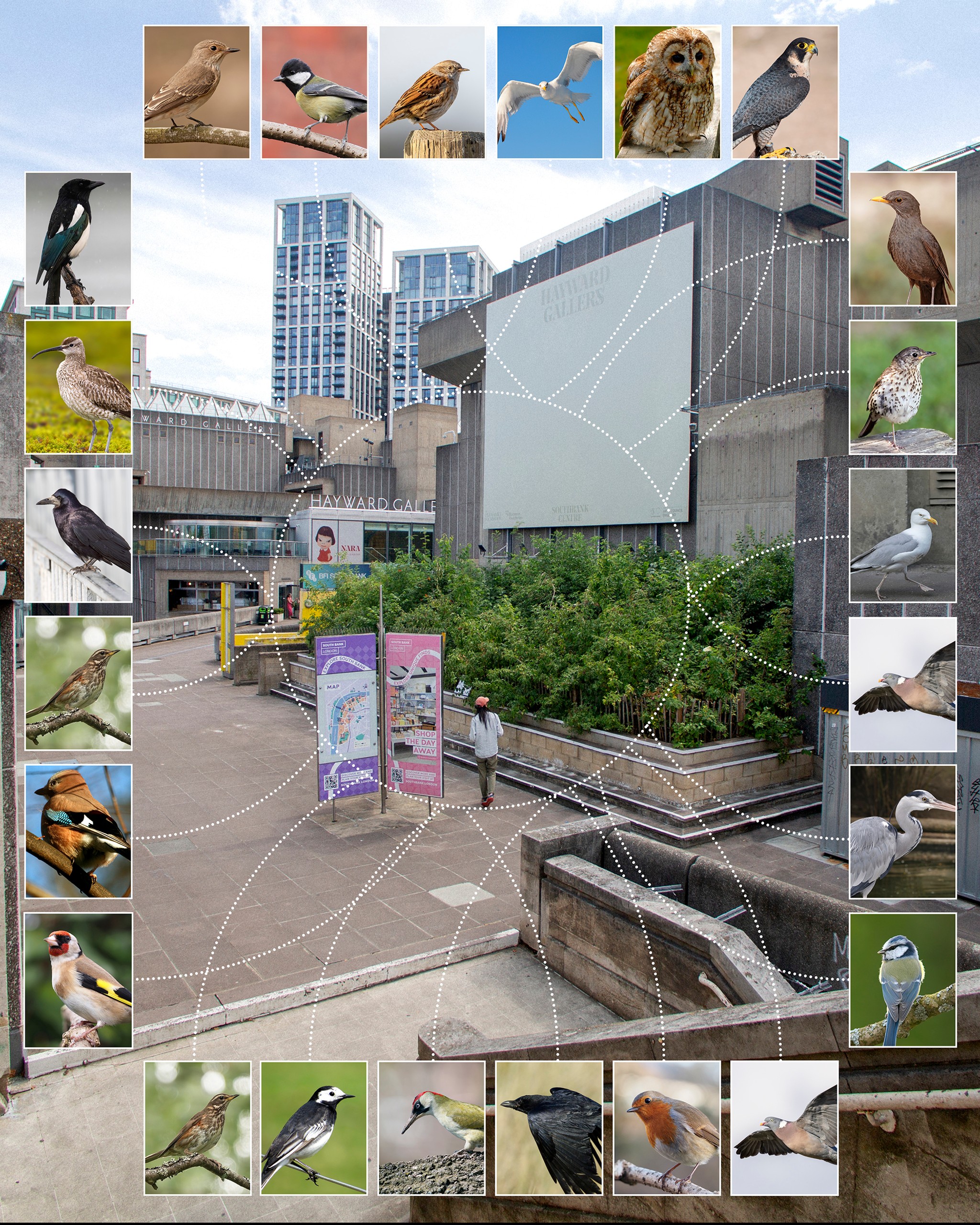

Figure 1: The three SUGi Pocket Forests and the nearby control sites selected for comparison in this study: Southbank Forest, Serenity Forest and Forest of Thanks

"We now have robust pilot evidence from almost 100 participants showing that just 30 minutes in a SUGi Pocket Forest significantly reduces anxiety compared with time spent in typical urban outdoor settings. Combined with early data on environmental gains (temperature, ecoacoustics) this forms a compelling case for their dual health-and-climate value. The next critical step is a scaled, policy-relevant study assessing all SUGi Pocket Forests in the UK (and a global sample) using consistent methods, paired with health-economic analysis to quantify the real cost–benefit impact of integrating pocket forests into urban environments."

— Kathy Willis, Professor of Biodiversity in the Department of Biology and the Principal of St Edmund Hall, University of Oxford.

Psychological well-being

To assess whether sitting near the pocket forests reduced participants’ anxiety, we used the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), a standard clinical questionnaire. The STAI measures how anxious a person feels using 20 multiple-choice questions and produces a score between 20 and 80, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety and more negative emotions.

Participants completed the questionnaire before and after spending 30 minutes at both the control site and the Pocket Forests. Clear differences emerged (Fig. 2). After time in all three pocket forests, participants’ anxiety scores were significantly lower than after spending the same amount of time at the control site. Statistical analysis showed that these reductions were unlikely to have occurred by chance.

Figure 2: Boxplots show the percentage change in STAI scores from pre and post sessions for each location at the Forest of Thanks (w=5, p=0.0026 , median difference=-6, n= 14), Serenity Forest (w=2 , p=0.0002 median difference =-10, n=19) and Southbank Forest (w =143 , p=0.0202, median difference = -4, n =33) sites. Individual points show individual participants. The dashed line at zero represents no change (0%). Negative change suggests that STAI (anxiety) scores were lower after the 30- minute intervention.

Physiological well-being

We assessed the impact of sitting near the SUGi Pocket Forests on physiological well-being using two measures: heart rate and heart rate variability. Heart rate is the number of heartbeats per minute, and a decrease is a well-established clinical indicator of calming, reflecting changes in autonomic nervous system activity in response to stress. Heart rate variability is also an indicator of autonomic nervous system activity, capturing how much the time interval between successive heartbeats varies. In this study, we focused on heartbeats associated with parasympathetic nervous system activity, where higher values are a sign of physiological calming.

Participants recorded heart rate and heart rate variability using a mobile phone app (Welltory) before and after spending 30 minutes at the control site and then for a similar interval of time sitting near one of the three SUGi Pocket Forests.

Figure 3: Boxplots show the percentage change in heart rates (HR) (bpm) from pre and post sessions for each location at the Forest of Thanks (w= 21, p= 0.6797, median difference= +6.017% n=8), Serenity Forest (w= 67, p= 0.9799, median difference = - 1.2887%, n = 16) and Southbank Forest (w= 20, p= 0.0209, median difference = -11.2980%, n= 14) sites. The dashed horizontal line indicates no change (0%). Individual participant data are shown as jittered points. Negative percentage change indicates heart rates (bpm) decreased after the 30-minute intervention.

Heart rate

Results from the heart rate measurements showed significant differences between sites (Fig. 3). After time at the Southbank Forest, participants’ heart rates were lower than at the corresponding control site, indicating physiological calming. In contrast, there were no significant differences between the pocket forests and their control sites at either Forest of Thanks or Serenity Forest.

This may reflect the fact that the control sites for Forest of Thanks and Serenity Forest still involved some interaction with green space and trees, as shown in the photos (Fig. 1). By comparison, the control site for the Southbank Pocket Forest, in central London, was an area dominated by concrete with very little vegetation.

This result warrants further investigation, especially because a similar pattern appeared in the heart rate variability measurements. At the Southbank Forest, there was a significant increase in parasympathetic activity, another strong indicator of physiological calming, whereas no such change was observed at the other two sites (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Boxplots show the percentage change in rMSSD (ms) from pre and post sessions across sites for each location of Forest of Thanks (w=14, p= 0.5337, median difference = -25.4980%, n= 7 ), Serenity Forest (w= 51, p= 0.3634, median difference= 47.1230%, n = 13) and Southbank Forest (w=71, p= 0.0067, median difference = 77.0832%, n = 12). The dashed horizontal line represents no change (0%). Individual participant data are shown as jittered points. Positive percentage change indicates that rMSDD (ms) increased after the 30-minute intervention.

Conclusion

Preliminary findings from this pilot study, involving 75 participants across three SUGi Pocket Forest sites in the UK, suggest that spending as little as 30 minutes sitting at these pocket forests, compared with nearby control sites, reduces anxiety and, at the Southbank Forest, also promotes physiological calming. These results highlight the potential physical and mental health benefits of this form of urban green infrastructure and justify further research, including work across a wider range of SUGi Pocket Forest sites, in different seasons, and cultural settings.

References:

Willis, K., (2024), Good Nature: The New Science of How Nature Improves Our Health, London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 336 pp, ISBN 9781526664907