What Is Biodiversity?

Biodiversity is the term given to describe the amazing array of different lifeforms that you can find on Earth or in a given place or habitat at a moment in time, from animals to plants, fungi to other microorganisms.

You need biodiversity or ‘the biological variation of life’ for an ecosystem to flourish because it’s precisely this mix of species in a particular environment that creates an ecosystem in the first place.

You can think of biodiversity like cogs in a machine. The machine is the ecosystem, and the cogs are all the different species that make up that ecosystem. If you remove one of the cogs (or one of the species), then the machine starts to fail. If you remove them all, the machine (or ecosystem) collapses altogether.

This same metaphor can be applied to a Jenga game. Each block represents a lifeform, and the accumulation of blocks represents biodiversity. Without the blocks, the tower wouldn’t exist, and the more blocks you remove, the more unstable the tower becomes.

Healthy ecosystems need biodiversity because every animal, plant, fungus, and microorganism support and interact with each other in an intricate web of life. Every living thing fulfils an important function that enables the entire ecosystem to thrive, providing food for the next link in the food chain and helping to create the environmental conditions required for survival.

Biodiversity supports everything within nature that we need to live – food, clean water, clean air, medicine and shelter. Humans are part of nature, part of an ecosystem and part of a food chain. So as SUGi forest maker Ethan Bryson explains, “It’s [also] critical for our survival on this planet that we pay sufficient attention to enhancing biodiversity in a way that enhances life.”

Biodiversity within the forest

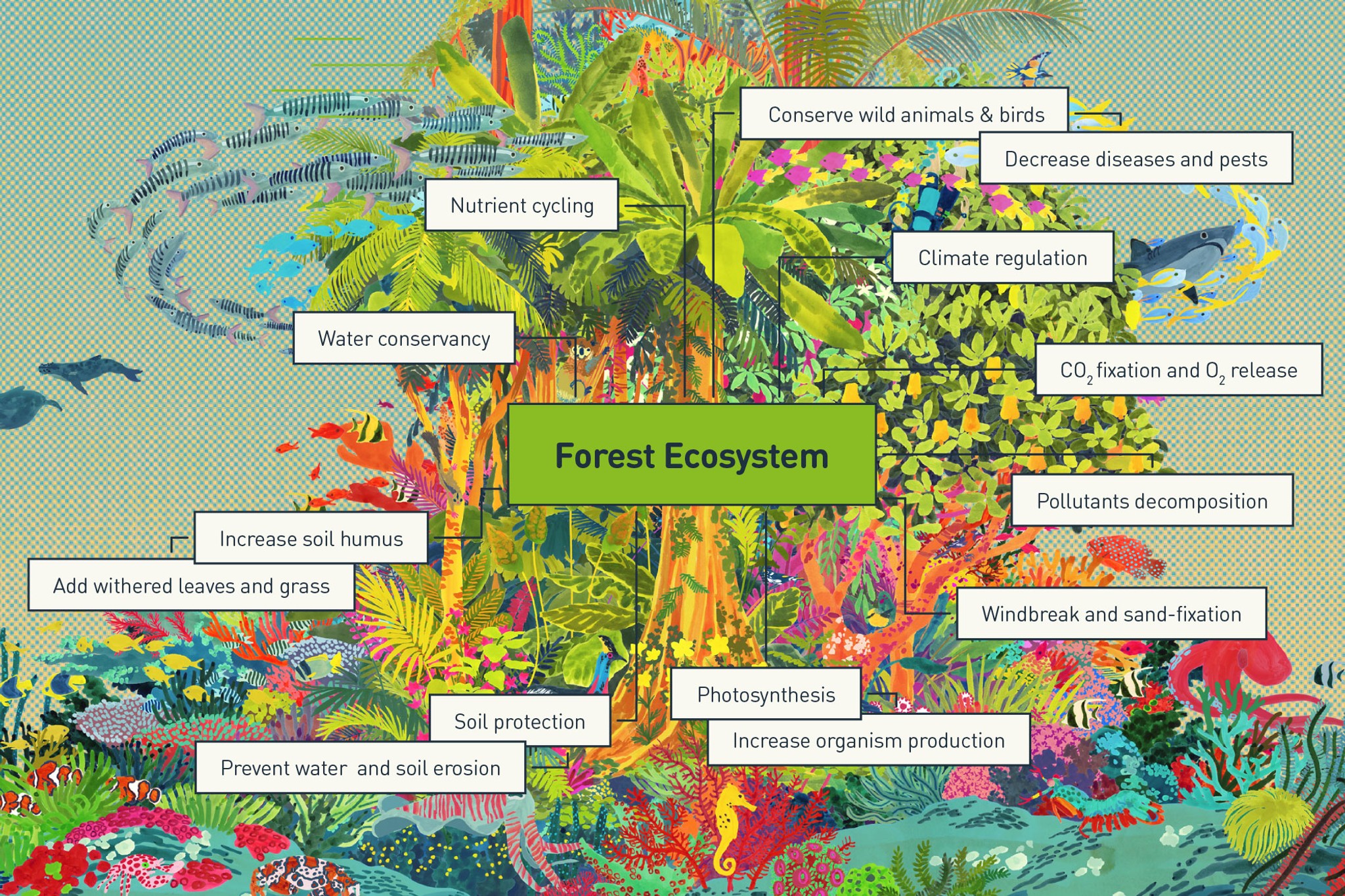

Forests are vital for biodiversity, as they’re home to more than three-quarters of the world’s life on land. But forests don’t just provide a habitat for an astonishing abundance of wildlife; this diversity of life enables the forest to exist in return.

People often ignore the forest for the trees, but it’s a mistake to view forests as simply individual trees. A forest is a single living entity or a community of organisms interacting and supporting each other in an interconnected network. In a thriving forest, you will find biodiversity in the soil, on the forest floor and high up among the leaves.

A diverse soil food web marks the start of the food web and is where decomposition happens. Trees shed their leaves, and dead wood falls to the ground, creating a litter of organic matter on the forest floor. It’s here that the community of decomposers, from fungi and bacteria to termites, earthworms and millipedes, get to work. Decomposers play a crucial role in nutrient cycling and retention, water cycling, waste management, pollution and pathogen control. Mycorrhizal and saprophytic fungi and bacteria break down organic material. These fungi then store the nutrients in the soil in long branching bodies, maintaining soil structure and water retention, holding carbon and preventing soil erosion. Predators such as protozoa and nematodes eat fungi and bacteria, releasing nutrient-rich faeces that plants and trees then absorb to help them grow.

Recent scientific discoveries show that trees have a vital, millennia-old relationship with mycorrhizal fungi, which live and grow in association with their roots. These “fungus roots” have branching threads, or mycelium, that spread from the root tip of one tree (or plant) to connect with the roots of others in a vast Wood Wide Web. The Wood Wide Web enables trees to communicate and pass resources between each other.

But biodiversity isn’t only essential in the soil and on the forest floor; a rich mixture of life is also needed in the canopy. Pollinating birds, bats and insects enable plants and trees to breed, create seeds and pass on their genetic material. Birds and mammals enable the dispersal of plant and tree seeds, gorging on fruits and nuts, and predators maintain the balance of the food chain, managing pests by eating invertebrates that may decimate tree populations. Plants create oxygen, clean air, water, food, shelter and medicine, enabling all animals to survive.

Why is biodiversity important?

As you can see, without biodiversity, you would not have a forest. Biodiversity builds health, resilience, adaptability and stability.

There is a complex balance between species that have evolved together to make up a temperate forest, a tropical rainforest or a boreal forest. And the organisms involved in a forest ecosystem are interdependent on one another for survival.

More species variety and variability reduces the chance for pests, diseases and natural disasters to wipe out an entire habitat. If one species starts to struggle, another with a similar ecological niche can step in and keep that part of the system functioning. But if biodiversity is lost, and fewer and fewer species can fulfil a particular niche, the ecosystem will begin to collapse.

More biodiversity within a forest essentially means more food and more diverse habitat for a wider variety of wildlife. As SUGi forest maker James Godfrey-Faussett explains, “Biodiversity allows a forest to function at its optimum level. If you have the diversity of species, all the tools that nature might need to adapt to climatic changes are there. To adapt, they need these tools.”

Imagine if you took a human out of their support network and slowly removed their ability to communicate, access food and water, and exposed them to more pathogens. That person would find it much harder to rise to difficult challenges. A similar thing happens when biodiversity is lost.

Therefore, protecting biodiversity can help us adapt to and tackle climate change. Healthy, biodiverse ecosystems can regulate our climate and rainfall and supply the ecosystem services needed to prosper and survive – such as clean water, clean air, food, medicine and shelter. A diverse forest will also grow faster and sequester more carbon.

SUGi builds biodiversity using the Miyawaki Method

It’s impossible to tackle climate change without addressing biodiversity loss, but at the same time, biodiversity loss is happening as a result of climate change. Most of the factors associated with the decline of forest biological diversity are of human origin.

Biodiversity is being destroyed in the forest due to the conversion of forest to agricultural land, overgrazing, unsustainable forest management, the introduction of invasive species, pollution, climate change and mining and oil exploitation.

So it’s essential that we don’t just plant trees but restore the forest ecosystem. Building biodiversity lies at the heart of SUGi, and we restore habitats by planting pocket forests using the Miyawaki Method.

The Miyawaki Method creates urban pocket forests that are 30x denser and 100x more biodiverse than their conventional counterparts. A mixture of 3-4 native saplings is planted per sqm.

The Miyawaki Method builds biodiversity by planting a large mix of native trees. High biodiversity is found in native forests due to the long association between the species. There has been a co-evolution over millennia between host plants, their predators, pollinators and their epiphytes. Local species have become reliant on native host plants for food, breeding sites and shelter.

Saplings planted using the Miyawaki Method are also planted close together and are multi-layered with canopy trees, sub-trees and shrubs. Because of this denseness and layering, there is more shade and habitat for wildlife. More fruit and seeds provide a food source for hungry birds, insects and mammals, and increased leaf litter feeds a growing soil food web.

“The diversity and proximity of multi-layered forests encourage competition but also collaboration for resources. As the multi-layered habitat, including the life in the soil, proliferates at an accelerated pace, you have more water retention in the soil, healthier soil biology, and therefore healthier and deeper root systems.”

SUGi forest maker, Ethan Bryson